Did this ancient Egyptian woman play an important economic role?

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Tjat attends Khnumhotep and his family.

The caption above her refers to her as “sealer, keeper of the property of her lord, Tjat, born of Netjeru.”

Image copyright Melinda Nelson-Hurst

Upon entering tomb 3 at Beni Hasan, I was struck by the beautiful preservation of the wall paintings. The overwhelming, large presence of the tomb’s owner, Khnumhotep II, on every wall was impossible to miss, but who were the rest of these people shown on the tomb walls? While my interests can be somewhat broad, what really drives me in my research is wanting to know about not just the prominent kings and government officials, but other people too, especially families and their less-studied members.

As I have discussed in previous posts, the woman named Tjat and her sons, who appear multiple times in the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan, sparked my interest and a new avenue of research that is now destined for multiple articles. Tjat appears four separate times among the beautiful wall paintings in Khnumhotep II’s tomb. Her prominence in his tomb, among other factors, led scholars to the assumption that Tjat was the mistress (later, second wife) of Khnumhotep II. For more on Tjat see my first post in this series, and see the second post for more on her sons.

In this post, rather than focusing on what Tjat may not have been (i.e., Khnumhotep’s mistress), I want to focus on what we can say about her position within the house of Khnumhotep.

What is a “house” exactly?

First, I should clarify what I mean by “house.” This is a complicated subject, but I’ll keep it short. When I say “house” here, I refer to the anthropological idea of the “social house.” A social house can encompass a location, physical property (a house and other goods), and people (those who reside in the same residence and sometimes those who do not). These people in the “social house” could include both those with and those without family ties to the main family who resided within the primary house structure. Thus, the house could include people such as domestic servants and those who did not live in the same building, but who were part of the same group of people, sometimes through work connections (colleagues, subordinates, etc.). I use this definition for house here in describing Tjat to suggest that, while she played a role in Khnumhotep II’s house, she may not have lived within the same building as Khnumhotep II or have been related to (or in a sexual relationship with) him. This is an important distinction to make when discussing what Tjat’s role was and why she was important enough to appear in the tomb of Khnumhotep II in four separate places.

Basic ancient Egyptian hieroglyph for a house structure, which could also be used sometimes to refer to a group of people.

What role did Tjat play within Khnumhotep’s house?

Tjat is labelled almost exclusively as a female “sealer” (khetemtet), but what does such a title actually mean? We are not entirely sure of the answer to this question because only a very small number of women appear in the historical record with this title, and even fewer from the same period as Tjat (the Middle Kingdom). A much larger number of men are recorded as having held the title of sealer (khetemt) or a related title. However, simply because the two titles are the same (with the exception of the feminine ending added for women) does not mean that the duties carried out were the same. Even among male sealers, their duties and pay may have varied.

I said I would be sticking to what we can say about Tjat, though, right? To do so, let’s take a look at what it meant to seal something in ancient Egypt.

What does it mean to “seal” an item?

When I say “seal,” I do not mean to lock or secure something so that it cannot be opened. Instead, I refer to the ancient Egyptian practice of placing globs of mud across where storage containers and doors were tied closed. Mud, of course, is not going to keep anyone out of a room or prevent them from opening a letter. However, if you stamp that mud with your name or personal design, anyone who looks at the item will know if it is still sealed the way you left it, or if someone has tampered with the seal. A similar practice is still sometimes used today in Egypt, but with wax on top of a lock, rather than mud on a cord or other material.

Clay seal impression found under the door of the Tomb of Nespekashuty at Deir el-Bahri, Thebes, Egypt. 11th Dynasty.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.3.150, Rogers Fund, 1926.

Permalink: http://metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/561798

This practice can be likened to that of using wax impressed with a personal seal over the flap of an envelope from the Middle Ages until quite recently (and some people are still into this practice, as a quick Internet search will demonstrate). Like ancient Egyptian mud seals, wax could not keep someone from opening an envelope, but it would be evident if anyone had read or otherwise tampered with the letter since it had left the sender’s hands.

A broken wax seal on a letter from Loudoun Castle, Galston East Ayrshire, Scotland.

This image is in the public domain.

For an even more modern analogy, just think of that bottle of vitamins or soda you bought – you had to break a seal to open it, didn’t you? That little plastic or metal seal around the cap can’t keep you from opening the bottle (at least it is not supposed to, but these things can be quite annoying at times), but you would know if someone else had opened it before you, whether for nefarious reasons or not.

Aluminum bottle with threaded screw cap and safety ring. Even if you were to replace the cap, it would be evident that the bottle had been opened because the ring is no longer attached to the cap.

Image licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Turning back to ancient Egypt, mud seals were used on a variety of items, everything from door handles to papyrus letters. The seals that left these impressions in the mud were usually made of stone or faience and carved into the shape of a scarab beetle (during the time in question; there were seals of other shapes and styles during other periods). These scarab seals had a flat bottom, on which a name and title or a decorative design was carved. Many such seals have been found, but because they were not discarded regularly like the globs of mud with seal impressions, they are typically found at archaeological sites less frequently than fragments of mud sealings with partial impressions (almost everything we find in archaeology, especially in household contexts, is broken – that’s why the ancients threw it away!). It seems that these seals were sometimes worn by their users, as one can see from the below example.

Scarab finger ring of the chamber keeper Ameny, from Lisht North, south of Tomb of Nakht (493), south cemetery, Pit 453. 12th-13th Dynasty.

Metropolitan Museum of Art 15.3.135a, Rogers Fund, 1915.

Permalink: http://metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/546686

The impressions left in the mud by stamp seals can tell us a lot about the activities that particular people carried out at a site or who was sending goods or letters from far away. Where mud sealings are found at an archaeological site is assumed to be the location where an item was opened (thus breaking the seal) because the seal would be broken and discarded upon opening, which may or may not have taken place at the same location as where the item was sealed. Some items were repeatedly opened and closed at the same location, while others were delivered from another location.

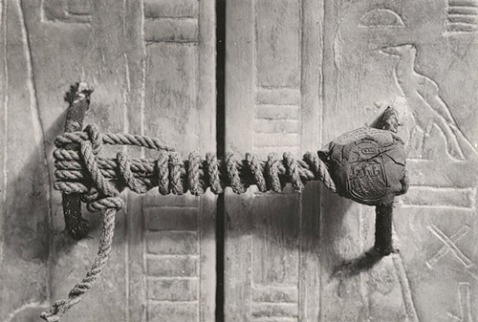

Unbroken seal on Tutankhamun’s third shrine before it was opened.

Photograph taken by Harry Burton in January 1924.

Published online in “Harry Burton: Unbroken Seal on the Third Shrine” (TAA622) In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/TAA622. (January 2009)

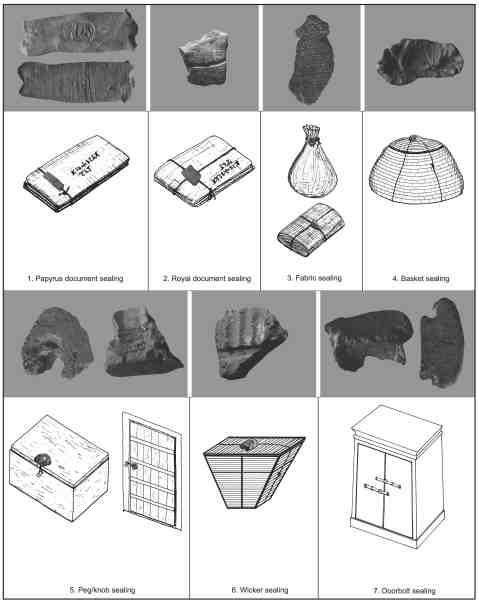

The impressions that these various sealed items left in the mud often show us what type of object the mud sealing had secured. Impressions from pegs (usually with additional impressions from twine) indicate the sealing mud had been affixed to the closing mechanism of a door or box. An example of how this type of sealing was used comes from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Howard Carter found Tutankhamun’s tomb mostly intact in 1922. When Carter and his associates eventually worked their way into the burial chamber, they discovered that multiple shrines (large, rectangular enclosures) surrounded the king’s sarcophagus. In photographs from the excavation, we can see on the third of these shrines that the opening was still sealed with rope and a mud seal. In this case, the rope is tied around two metal half circles, but it functioned the same way as if it were attached to two pegs/nobs.

Outside of such a royal context, seals were used to secure a variety of items, including papyrus letters, jars filled with food items, and boxes, baskets, and rooms that contained various forms of personal wealth, such as jewelry, linen, mirrors, and even cosmetics – the stuff of everyday life among the upper classes in ancient Egypt.

The impressions (or “sealing back types”) left by a variety of sealed items.

Illustration copyright and courtesy of Josef W. Wegner.

While direct information on Tjat and her career is limited, we can infer from her title as a sealer that she was involved in regulating and securing items of some value in the house of Khnumhotep II. She is even labelled in the tomb once as “keeper of the property of her lord (i.e., Khnumhotep).”

What exactly she sealed in this capacity we may never know for certain, but in a future post we will explore some possibilities. Whatever the particulars, though, it seems clear that Tjat’s position within the house of Khnumhotep was an important one that encompassed economic responsibilities within what was likely one of the wealthiest houses in the country.

“Son of a count!”

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

“Son of a count!”

No, this isn’t an ancient Egyptian swear. It’s the phrase that sometimes labels sons of the female administrator named Tjat in the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan. In a recent post, I discussed the interpretation of Tjat’s role in Khnumhotep’s household and my doubts about her having been the mistress or second wife of this man.

There are many pieces of evidence that scholars have mentioned or which could be pointed out as a justification for the idea that she and Khnumhotep II had a sexual relationship. The best and most commonly cited evidence are the following factors: Tjat’s two sons are sometimes labelled “son of a count” (sȝ ḥȝti-ʿ), Tjat and her sons take a prominent place in multiple scenes within Khnumhotep’s tomb, and Tjat’s son Khnumhotep IV started building a massive tomb next to that of Khnumhotep II (it was left unfinished). In this post and future ones, I will address each of these pieces of evidence, as well as some more minor ones, and how they fit into the larger context of ancient Egyptian social, artistic, and writing conventions.

We know that Tjat had at least two sons because these sons are described as being born by Tjat. It is helpful that during the Middle Kingdom ancient Egyptians had a preference for recording their mothers’ names with their own in this fashion, but this only gets us so far, as in most cases the name of the father is not mentioned. Because of this ambiguity, we often are not able to identify a person’s parentage with certainty. Thus, other evidence – such as artistic conventions for where and how people are depicted in tomb scenes or the administrative titles that people held – is often used to try to fill in the gaps. The former practice can be decently reliable in some types of cases in which Egyptian conventions are well-understood and will be the subject of a future post. However, the latter can be more problematic. Today I would like to focus on the interpretation of the title (or, more accurately, “label”) “son of a count” as identifying Tjat’s sons – Khumhotep and Nehri – as sons of Khnumhotep II.

Following Khety’s sons, Tjat’s son Nehri stands at the far right. He is labelled: “Son of a count, Nehri, born by the sealer Tjat, true of voice.” (Newberry, Beni Hasan I, pl. XXXV)

I must start by saying that the use of the label “son of a count” for Tjat’s sons in the tomb of Khnumhotep II is decent evidence for a father-son relationship and is the best of all possible evidence for this relationship. However, that Tjat’s sons were sons specifically of Khnumhotep II is not the only option. To understand why, we have to take a step back and look at the Khnumhotep family as a whole (or rather, as whole as the evidence will allow).

First, one must note that every elder male member of Khnumhotep II’s family named in his tomb is said to be a “count” (more accurately rendered as either “mayor” or as a general term for a “high-ranking official,” depending on the context, but for the sake of consistency I will continue to translate this title as “count” here). This title is extremely common among the high elite in Middle Kingdom Egypt and often seems to denote a level of status or rank, rather than an administrative position with specific duties. Khnumhotep II and his male family members all have administrative titles that are more specific in addition to “count” in their titularies.

We do not know as much about the father of Khnumhotep II and his family as we do about Khnumhotep II’s mother’s family. However, we know that his father also held the title of “count” and that while he was probably from another area of Middle Egypt, he lived and worked near the capital of Itj-tawy when he married Khnumhotep II’s mother. In addition to the use of this title by his father, maternal grandfather, and maternal uncle, the mother of Khnumhotep II is called both “daughter of a count” (sȝt ḥȝti-ʿ) and “countess” (ḥȝtit-ʿ) in his biography. Thus, we know that both sides of his family used the title of “count” quite extensively, denoting their place in the high elite.

The Khnumhotep Family Tree. The men designated as “count” in Khnumhotep II’s tomb are shaded green. Copyright Melinda Nelson-Hurst.

Khnumhotep II’s wife, Khety, is also called “daughter of a count” and “countess.” We also know that she came from the ruling family in a neighboring nome (geographic district). The biography of Khnumhotep II states that his eldest son by Khety, Nakht II, took over the position of his maternal grandfather (Khety’s father), making him also a “count” and ruler of the neighboring nome. Therefore, we know from these texts that the Khnumhotep family was intermarried with high-ranking families of at least two other geographic areas, all of whom carried the title of “count.”

The commonality of the title “count” among these interconnected elite families means that Tjat could have been married to a family member of Khnumhotep II or Khety, who would have held the title “count” by virtue of the family’s status. In such a scenario, Tjat’s sons would still be related to Khnumhotep II (which also could account for their appearance in his tomb), but not as his sons. They could be his nephews, cousins, in-laws of some type, or even his grandsons. Of course, they might also be from an unrelated family, but that possibility seems unlikely, since Khnumhotep II was in some way related to multiple elite families (that is, the people who would hold the title of “count”) in the region surrounding Beni Hasan. Thus, the label “son of a count” by itself is not as solid evidence for Khnumhotep II having fathered Tjat’s children as it initially sounds, though it is still one of the possibilities.

Now that we’ve reached the end of this post, some of you may be thinking “But why, if Tjat were married, is she shown without a husband in the tomb scenes and does not carry the title of “lady of the house” (nbt pr) within Khnumhotep II’s tomb? These are questions that I will address in later posts.

Works referenced:

Newberry, P.E., and F. Ll. Griffith. Beni Hasan. vol. I, Archaeological Survey of Egypt 1. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, and Co., 1893.

A female administrator in ancient Egypt

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

The cliffs of Beni Hasan. Note the modern staircase on the right side, which leads to the level of the tombs of the nomarchs (local administrators). The tops of the doorways into the tombs are just visible from this angle. Image copyright Melinda Nelson-Hurst.

For a view from the air, see this pin in Google Maps.

The Khnumhotep family at Beni Hasan is well-known among scholars who work on the period of the Middle Kingdom and tourists who have visited Middle Egypt in modern times. The beautifully preserved decoration on the tomb chapels at this site has attracted a steady flow of visitors over hundreds of years. One of the best preserved among the tombs at this site is that of Khnumhotep II, a member of the local elite and its most powerful family. His tomb is also discussed quite often because of its unique scene of “Asiatic” traders, who have been variously interpreted as people from the Near East or nomads of the eastern desert of Egypt.

Line drawing of the scene of Asiatics in the tomb of Khnumhotep II (Newberry, Beni Hasan I, pl. XXXI)

Although less well known to tourists, the woman named Tjat who appears in the chapel wall decoration within this tomb at Beni Hasan has been mentioned frequently in scholarly works on the Middle Kingdom. Despite the frequent mentions, other than one article by William Ward, no one has focused much attention on her. She clearly played an important role in Khnumhotep’s household, as she is shown three times in his tomb: in close proximity to Khnumhotep himself in the fowling scene, with Khnumhotep’s wife and daughters in a funerary cult meal scene, and inside the shrine, next to the doorway and a distance behind Khnumhotep’s daughters.

Line drawing of Khnumhotep’s wife Khety sitting by a table piled high with offerings for her afterlife. Behind her stand her three daughters, Tjat with two children, and a nurse (Newberry, Beni Hasan I, pl. XXXV).

Because Tjat appears in such important positions within the tomb and her two sons are referred to as “son of a count” (“count” being a title that Khnumhotep II held), scholars have assumed that Tjat was the mistress of Khnumhotep II and mother of two of his sons and one of his daughters. The same assumption is often made in discussions of other artifacts on which women without a clear relationship to the primary man are shown in somewhat prominent positions, but are we too quick to make such an assumption? In my work on Middle Kingdom families, and on the Khnumhotep family in particular, I began to realize just how quick we, as scholars, have been to assume such a role for women when their positions are somewhat unclear. I decided that this was an issue that I should address in my work and thus my research on Tjat and women in similar situations began.

Line drawing of Tjat’s son Nehri following the sons of Khety (Newberry, Beni Hasan I, pl. XXXV)

Was Tjat Khnumhotep’s real love? Was she a servant taken advantage of by him? Or was their relationship something else entirely?

History (and even current events) provides many examples of men using their power to take advantage of women lower in the hierarchy than themselves, whether within their own households, in the modern workplace, or elsewhere. Undoubtedly, this sort of abuse of power would have happened in ancient times as well. In fact, some ancient Egyptian men even say in their biographies that they never did such a thing. One can surmise that, if they felt the need to distinguish themselves by pointing out how they had not done such deeds, the practice was not uncommon among other elite men. In addition, completely consensual relationships between such parties may have occurred.

But even if we accept that such relationships existed, must we assume that every prominent woman in a male-dominated context gained that prominence through a sexual relationship? At least for the case of ancient Egypt, I would argue “no.” While women’s roles in public and administrative spheres of life were restricted compared to those of men, women could still gain wealth, influence, and power through family relationships and their own professions (for example, as nurses for children of elite households or the royal family).

Line drawing of Khnumhotep II fowling (hunting birds). His wife Khety and an administrator accompany him, while Tjat and one of his sons (depicted behind Khnumhotep) wait on the river bank. In this scene, Tjat is labeled “treasurer, keeper of the property of her lord.” (Newberry, Beni Hasan I, pl. XXXII).

Coming back to Tjat, we know that not only was she prominent in tomb scenes, but she also held the position of “treasurer, keeper of the property of her lord.” As Ward pointed out, this appears to be a title that correlated to actual responsibilities in Khnumhotep’s household (keeping valuable property safe). But, at the same time, Ward stuck to the argument that Tjat was the mistress of Khnumhotep II. Despite the past and current consensus that Tjat was the mistress of Khnumhotep II, I think we must ask whether such a relationship is really the most likely cause of Tjat’s important place in the tomb decoration or whether there are other reasons. More to come on Tjat as my research continues…

Works referenced:

Newberry, P.E., and F. Ll. Griffith. Beni Hasan. vol. I, Archaeological Survey of Egypt 1. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, and Co., 1893.

Ward, William. “The Case of Mrs. Tchat and Her Sons at Beni Hasan.” Göttinger Miszellen 71 (1984): 51-59.