Did this ancient Egyptian woman play an important economic role?

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

Tjat attends Khnumhotep and his family.

The caption above her refers to her as “sealer, keeper of the property of her lord, Tjat, born of Netjeru.”

Image copyright Melinda Nelson-Hurst

Upon entering tomb 3 at Beni Hasan, I was struck by the beautiful preservation of the wall paintings. The overwhelming, large presence of the tomb’s owner, Khnumhotep II, on every wall was impossible to miss, but who were the rest of these people shown on the tomb walls? While my interests can be somewhat broad, what really drives me in my research is wanting to know about not just the prominent kings and government officials, but other people too, especially families and their less-studied members.

As I have discussed in previous posts, the woman named Tjat and her sons, who appear multiple times in the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan, sparked my interest and a new avenue of research that is now destined for multiple articles. Tjat appears four separate times among the beautiful wall paintings in Khnumhotep II’s tomb. Her prominence in his tomb, among other factors, led scholars to the assumption that Tjat was the mistress (later, second wife) of Khnumhotep II. For more on Tjat see my first post in this series, and see the second post for more on her sons.

In this post, rather than focusing on what Tjat may not have been (i.e., Khnumhotep’s mistress), I want to focus on what we can say about her position within the house of Khnumhotep.

What is a “house” exactly?

First, I should clarify what I mean by “house.” This is a complicated subject, but I’ll keep it short. When I say “house” here, I refer to the anthropological idea of the “social house.” A social house can encompass a location, physical property (a house and other goods), and people (those who reside in the same residence and sometimes those who do not). These people in the “social house” could include both those with and those without family ties to the main family who resided within the primary house structure. Thus, the house could include people such as domestic servants and those who did not live in the same building, but who were part of the same group of people, sometimes through work connections (colleagues, subordinates, etc.). I use this definition for house here in describing Tjat to suggest that, while she played a role in Khnumhotep II’s house, she may not have lived within the same building as Khnumhotep II or have been related to (or in a sexual relationship with) him. This is an important distinction to make when discussing what Tjat’s role was and why she was important enough to appear in the tomb of Khnumhotep II in four separate places.

Basic ancient Egyptian hieroglyph for a house structure, which could also be used sometimes to refer to a group of people.

What role did Tjat play within Khnumhotep’s house?

Tjat is labelled almost exclusively as a female “sealer” (khetemtet), but what does such a title actually mean? We are not entirely sure of the answer to this question because only a very small number of women appear in the historical record with this title, and even fewer from the same period as Tjat (the Middle Kingdom). A much larger number of men are recorded as having held the title of sealer (khetemt) or a related title. However, simply because the two titles are the same (with the exception of the feminine ending added for women) does not mean that the duties carried out were the same. Even among male sealers, their duties and pay may have varied.

I said I would be sticking to what we can say about Tjat, though, right? To do so, let’s take a look at what it meant to seal something in ancient Egypt.

What does it mean to “seal” an item?

When I say “seal,” I do not mean to lock or secure something so that it cannot be opened. Instead, I refer to the ancient Egyptian practice of placing globs of mud across where storage containers and doors were tied closed. Mud, of course, is not going to keep anyone out of a room or prevent them from opening a letter. However, if you stamp that mud with your name or personal design, anyone who looks at the item will know if it is still sealed the way you left it, or if someone has tampered with the seal. A similar practice is still sometimes used today in Egypt, but with wax on top of a lock, rather than mud on a cord or other material.

Clay seal impression found under the door of the Tomb of Nespekashuty at Deir el-Bahri, Thebes, Egypt. 11th Dynasty.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art 26.3.150, Rogers Fund, 1926.

Permalink: http://metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/561798

This practice can be likened to that of using wax impressed with a personal seal over the flap of an envelope from the Middle Ages until quite recently (and some people are still into this practice, as a quick Internet search will demonstrate). Like ancient Egyptian mud seals, wax could not keep someone from opening an envelope, but it would be evident if anyone had read or otherwise tampered with the letter since it had left the sender’s hands.

A broken wax seal on a letter from Loudoun Castle, Galston East Ayrshire, Scotland.

This image is in the public domain.

For an even more modern analogy, just think of that bottle of vitamins or soda you bought – you had to break a seal to open it, didn’t you? That little plastic or metal seal around the cap can’t keep you from opening the bottle (at least it is not supposed to, but these things can be quite annoying at times), but you would know if someone else had opened it before you, whether for nefarious reasons or not.

Aluminum bottle with threaded screw cap and safety ring. Even if you were to replace the cap, it would be evident that the bottle had been opened because the ring is no longer attached to the cap.

Image licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Turning back to ancient Egypt, mud seals were used on a variety of items, everything from door handles to papyrus letters. The seals that left these impressions in the mud were usually made of stone or faience and carved into the shape of a scarab beetle (during the time in question; there were seals of other shapes and styles during other periods). These scarab seals had a flat bottom, on which a name and title or a decorative design was carved. Many such seals have been found, but because they were not discarded regularly like the globs of mud with seal impressions, they are typically found at archaeological sites less frequently than fragments of mud sealings with partial impressions (almost everything we find in archaeology, especially in household contexts, is broken – that’s why the ancients threw it away!). It seems that these seals were sometimes worn by their users, as one can see from the below example.

Scarab finger ring of the chamber keeper Ameny, from Lisht North, south of Tomb of Nakht (493), south cemetery, Pit 453. 12th-13th Dynasty.

Metropolitan Museum of Art 15.3.135a, Rogers Fund, 1915.

Permalink: http://metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/546686

The impressions left in the mud by stamp seals can tell us a lot about the activities that particular people carried out at a site or who was sending goods or letters from far away. Where mud sealings are found at an archaeological site is assumed to be the location where an item was opened (thus breaking the seal) because the seal would be broken and discarded upon opening, which may or may not have taken place at the same location as where the item was sealed. Some items were repeatedly opened and closed at the same location, while others were delivered from another location.

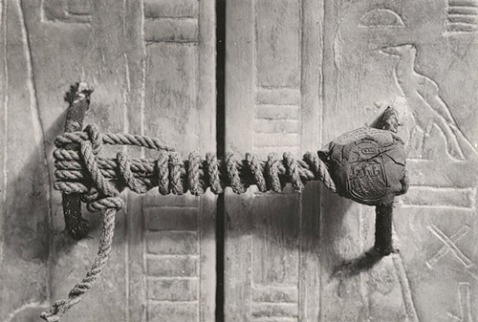

Unbroken seal on Tutankhamun’s third shrine before it was opened.

Photograph taken by Harry Burton in January 1924.

Published online in “Harry Burton: Unbroken Seal on the Third Shrine” (TAA622) In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/TAA622. (January 2009)

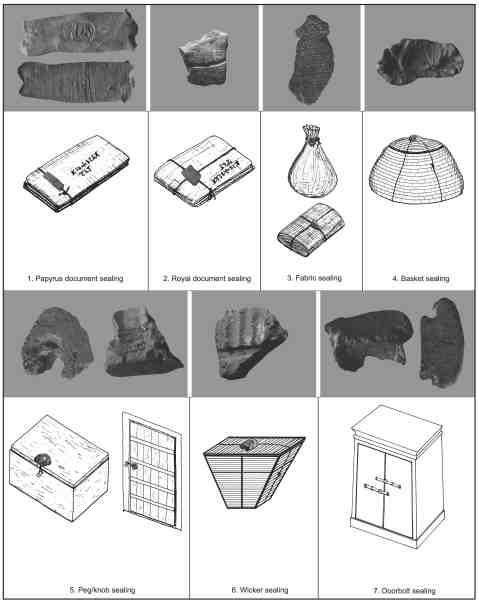

The impressions that these various sealed items left in the mud often show us what type of object the mud sealing had secured. Impressions from pegs (usually with additional impressions from twine) indicate the sealing mud had been affixed to the closing mechanism of a door or box. An example of how this type of sealing was used comes from the tomb of Tutankhamun. Howard Carter found Tutankhamun’s tomb mostly intact in 1922. When Carter and his associates eventually worked their way into the burial chamber, they discovered that multiple shrines (large, rectangular enclosures) surrounded the king’s sarcophagus. In photographs from the excavation, we can see on the third of these shrines that the opening was still sealed with rope and a mud seal. In this case, the rope is tied around two metal half circles, but it functioned the same way as if it were attached to two pegs/nobs.

Outside of such a royal context, seals were used to secure a variety of items, including papyrus letters, jars filled with food items, and boxes, baskets, and rooms that contained various forms of personal wealth, such as jewelry, linen, mirrors, and even cosmetics – the stuff of everyday life among the upper classes in ancient Egypt.

The impressions (or “sealing back types”) left by a variety of sealed items.

Illustration copyright and courtesy of Josef W. Wegner.

While direct information on Tjat and her career is limited, we can infer from her title as a sealer that she was involved in regulating and securing items of some value in the house of Khnumhotep II. She is even labelled in the tomb once as “keeper of the property of her lord (i.e., Khnumhotep).”

What exactly she sealed in this capacity we may never know for certain, but in a future post we will explore some possibilities. Whatever the particulars, though, it seems clear that Tjat’s position within the house of Khnumhotep was an important one that encompassed economic responsibilities within what was likely one of the wealthiest houses in the country.

Trackbacks / Pingbacks